What designers can learn from ethnography

This post will not give you methods and approaches to walk away with and apply to your work. Instead, it is a story about my experience at the Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference (EPIC) 2016 and how it confronted how I see my role as a designer, and continues to challenge me to be the best designer I can be.

Since working in service design, I find myself using terms like human-centred, customer-centred and empathy and saying things like “core to my design process is the need to understand the behaviours, values, aspirations, fears and motivations of the people I am designing for.” But the tension for me has always been, how can we truly empathise for people? What are the limits of our understanding? How can we as designers equip ourselves with the tools, lenses and experiences to be able to gain rich insights into the people we are designing for?

I believe that because I design for people, with people, it was my responsibility to figure out what the best ways were to dig deeper, so I can get rich insight into the human experience – how other people experience the world; realities that are not my own. After all, our insights into how people behave, their attitudes, rituals, dreams and fears inform and inspire the products and services we design. I obsess over this (and many other things), so I can be the best designer I can be.

With this goal in mind, I attended the Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference (EPIC) in Minneapolis in September this year. The EPIC conference is run by a diverse community of practitioners and scholars from technology organisations, product and service companies, a range of consultancies, universities and design schools, government and NGOs, and research institutes. The purpose of the conference is to advance the value of ethnography in industry, so the hook for me, was it’s grounding in the discipline of anthropology.

This was important because simply put, anthropology is the study of people – both biologically and socially. Anthropologists take the time to study the everyday lives of people to uncover rituals, behaviours, language and values in order to explore what makes us uniquely human and increase our understanding of ourselves and of each other. They ask questions like how are societies different and how are they the same? how has evolution shaped how we think? what is culture? are there human universals? (Royal Anthropological Institute, 2017). As a designer, what they do jumps out to me and excites me – the discipline and practice has years of experience in gaining insight into people. It is a narrow slice of what we do as designers, but it is a very important slice. So, in my quest to better understand people, it felt like attending EPIC would help me in this exploration.

Armed with these expectations, I confidently sat in the auditorium, eager to hear the first presentation. By the time it was time to get tea and coffee, I felt confused, but not sure why. As the day went on I still felt confused – there was a disconnect between what I was expecting to hear and learn and what I was being confronted by.

This years conference was Pathmaking. The conference was exploring the paths being made between ethnography and business, academia and the reality of organisations. Ethnography has made inroads into business before this, but it felt like now, the spotlight was back on their discipline, but wrapped up in the practices of ‘design thinking’. This raised concerns about how ethnographic methods were being appropriated within business, and more specifically, design.

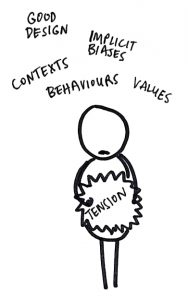

Sitting in the auditorium, I waited to hear about ethnographic methods to share with my team. Instead, I was confronted with philosophical questions. Are we (as designers) compromising our understanding of the people we are designing for, in an effort to fit within organisational timeframes and budgets? In conducting research for our clients, do we have implicit biases that impact how we design and conduct our research? Are we seeing what we want to see, and therefore, are we misrepresenting the people we seek to understand? Are we doing research the right way? Is there even a right way of doing research?

Baffled and confused, I paused and reflected. I remember sitting in the auditorium during the breaks, not talking to people, and I didn’t know why. As the conference went on, the why became clearer as fellow designers made their way onto stage and opened with “I have a confession to make, I’m a designer.”

Their comments felt honest, and resonated immediately. I heard myself saying the same thing in conversations the following days, meeting new people and feeling like I had to clear the air that I was a designer. I realised that I was questioning the validity of my practice as a designer. I felt that the rigour and the richness of insights that was evident in ethnographic practice was not in mine (relative to theirs!) – largely due to the context in which design operates and the budgets and timeframes we need to adhere to. But even so, I felt it. Despite the difference in purpose and contexts of design and ethnography, I still believed that a rigour and willingness to deeply understand people was an important part of being a designer. Ethnographers heeded warnings about flattening the user experience –presenting the human experience simply as an interaction between a user and a product or service. They spoke about the difference between understanding meaning, versus noticing and describing details (full conference proceedings here). There was a lot to learn from ethnographic approaches and methods, and their mindset - and I still need to seek this out and wrap my head around it.

But, I hold this tension within me because it feels important to, it keeps me honest. The experience provoked a deep reflection on my role as a designer. In designing products and services for people, in partnership with the organisations that deliver them, I believe we have a responsibility to deeply and rigorously seek to understand the people, contexts and behaviours we are designing for, challenge the assumptions of our clients and the contexts in which we are being asked to imagine and build, but more importantly ourselves – our biases, values, and our take on what good design looks like.

To this day, I hold the tension I felt at the EPIC conference to remind myself to challenge my assumptions, make my implicit biases explicit, and to ensure I am aware of the values I am embedding in the designs I imagine and build, so that I can be the best designer I can be. I have learned that implicit biases can easily leak out of us and into products and experiences that affect many, and could potentially exclude many. It is our responsibility to design products and services with a heightened awareness of the behaviours, experiences, communities, and cultures we shape with our designs.

With great power comes great responsibility. I am still learning how to be the best designer I can be, and what a great designer even looks like. How do you challenge yourself to be the best designer you can be? What tensions do you face as a designer seeking to improve the world we live in? What does a great designer look like for you? I’m really interested to hear your stories. Thank you for reading mine.